One week after the 2016 Presidential election, I visited Centre College in Danville, Kentucky. Both of my daughters are Centre graduates and daughter Leigh was on staff there. The reason for my visit was that Wendell Berry—poet, essayist, novelist and farmer—was to speak. Like many of the crowd gathered in the auditorium, I was hoping to find some comfort in his words.

One week after the 2016 Presidential election, I visited Centre College in Danville, Kentucky. Both of my daughters are Centre graduates and daughter Leigh was on staff there. The reason for my visit was that Wendell Berry—poet, essayist, novelist and farmer—was to speak. Like many of the crowd gathered in the auditorium, I was hoping to find some comfort in his words.

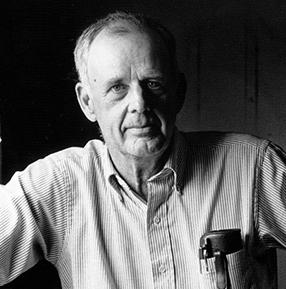

Berry is a rock star among Appalachian writers, though he would almost certainly shun that description. “I have no appetite for glitz and glamour,” he once said. Born in 1934 in Henry County, Kentucky, Berry is a graduate of the University of Kentucky. He spent more than two decades teaching English at Stanford University, New York University and at his alma mater. Eventually, he gave up the academic life and returned to Henry County, content to spend his time farming, writing and advocating for causes he believes in.

Those causes include environmentalism, self-reliance, loyalty to family and community and opposition to war and to agribusiness. Berry and his wife Tanya, to whom he’s been married for more than 60 years, have two children. The couple farms 125 acres of good dirt, growing much of what they eat and relying, whenever possible, on horses rather than machinery. They live without a television or a computer. Berry does all his writing by hand or on a manual typewriter, usually during daylight hours to reduce his reliance on electricity derived from strip-mined coal.

I first became a fan of Wendell Berry when I discovered what is arguably his most famous poem, “The Peace of Wild Things.” Here’s how it goes:

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be

I go and lie down where the wood drake rests in his beauty on the water

and the great heron feeds

I come into the peace of wild things

Who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief

I come into the presence of still water

And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light.

For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

As to whether Wendell Berry brought comfort to me or anyone else in the crowd on that November night, it’s hard to say. He, too, was disappointed and discouraged about the outcome of the election. “If you’ve lost the capacity to be outraged by what’s outrageous, you’re dead,” he said. “Somebody ought to come and haul you off.” I like that.

In the time since, Wendell Berry has brought me comfort in other ways, too, one of which is the documentary “Look and See,” showing now on Netflix. Another is a novel I’ll write about next week.

(March 3, 2019)