I’m a month late to the birthday party, but I’m celebrating anyway.

I’m a month late to the birthday party, but I’m celebrating anyway.

“The Great Gatsby,” regarded by many modern critics as a literary masterpiece and perhaps even The Great American Novel, flopped when it was released on April 10, 1925. Unlike F. Scott Fitzgerald’s previous novels, enthusiasm for “Gatsby” was so lukewarm—it sold only 20,000 copies during Fitzgerald’s lifetime—that the author went to his grave in 1940 considering himself a failure.

He didn’t know, of course, that World War II would change that. When the Armed Services division of the Council of Books in Wartime chose to publish “Gatsby” in paperback form and distribute it to soldiers, it was a huge and immediate hit.

The novel has now sold more than 30 million copies.

I can’t remember if I read “The Great Gatsby” in high school. If so, it was forgotten in favor of books I really loved: Lord of the Flies. A Separate Peace. Catcher in the Rye. Animal Farm. Huckleberry Finn. The Good Earth. Fahrenheit 451. The Old Man and the Sea. To Kill a Mockingbird. The Grapes of Wrath.

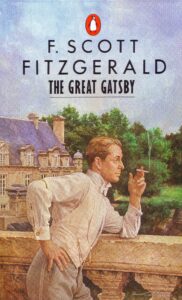

I know for sure that I read “Gatsby” several years ago for a book discussion group, but I don’t recall much about what was said. The novel’s 100th birthday seemed the perfect time for a revisit. As luck would have it, I found a used copy for sale at the library near my daughter’s home in Colorado. It’s a “pocket-size” Penguin paperback, not much bigger than those distributed to World War II soldiers. Its corners were curled and its pages yellowed and it smelled exactly the way I like a book to smell. Old. The cover featured not the well-known disembodied eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleberg but a painting of a handsome young man I assume to be Gatsby himself, casually leaning against a veranda rail with cigarette in hand.

This small book—only 172 pages and fewer than 50,000 words–would be the ideal way to entertain myself on the plane ride back to Tennessee, I decided. Best of all, the price was right: one dollar. So I bought it and read it. And was completely blown away.

Obviously, Fitzgerald couldn’t see the future. He was writing about the Jazz Age during the Jazz Age. He couldn’t have known that the stock market would crash before the decade ended. He couldn’t have known that the United States and the world would descend into a Great Depression. He couldn’t have known that the “War to End All Wars” didn’t. He couldn’t have known that evil men would deliberately and seemingly with relish murder millions of “undesirables” and cost millions of soldiers, sailors and airmen their lives when the world went to war again.

But he could see the emptiness in a society trying to recover not only from the previous world war but also from a flu pandemic that took 50 million lives worldwide. It was a society where the rich got richer and didn’t give a care about what was happening to anybody else. A society where the glittering façade of enormous waterfront mansions and fancy clothes and fancy cars and fancy food and limitless amounts of bootlegged liquor seemed to be enough.

A society where a once-poor man named Jay Gatsby, who knew–deep down inside–that his newfound wealth would never be enough to win the heart of Daisy Buchanan never stopped trying anyway.

“The Great Gatsby” is a sad, sad story. A story of selfishness and emptiness and waste. A story of seeking but never finding. A story that, a century later, still rings true because the things it tells about are still happening. Perhaps more so now than then. Is it the Great American Novel? Is there even such a thing as the Great American Novel?

I can’t answer those questions. But I can say I’m exceedingly glad I took the time to read “Gatsby” again.

(May 10, 2025)